Books

The Interpreter from Java

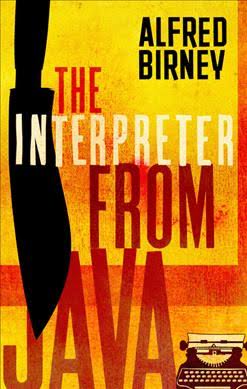

The Interpreter from Java by Alfred Birney, translation: David Doherty

(Head of Zeus, 2020)

From the first sentence, which barrels ahead at a feverish pace for more than one page, this novel grabs the reader by the throat.

A son compresses his father’s life in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) into one furious eruption — everything from the atrocities of the Japanese occupation, and the war of independence that followed, to his father’s violent and unpredictable treatment of his children in his new homeland, The Netherlands.

Arto Nolan is the father’s name; his son Alan strives to overcome his loathing and comprehend the man who abused him and beat his mother. That strange fellow from Indonesia had fled to the Netherlands before the Indonesians could execute him as a traitor. He soon married an overweight girl from a small town, had five children, and soon became so violent that Alan and his siblings had to spend most of their childhood in boarding schools.

His father spent evening after evening typing on his Remington; his wife and children had no idea what he was working on and were happy to have him out of the way. Later, Alan discovers his father had been working on his memoirs. Early in the book, he presents passages with his own sarcastic annotations – clearly, he does not have one shred of trust in his father. Later, his bitter interruptions become less frequent. They are completely absent from the second part of the memoirs, about Arto’s ruthless work as an interpreter who not only translated but also led interrogations, tortured prisoners, and did not hesitate to murder.

Arto’s passages are chilling in their detachment. He first describes how he was abused as a child by his own father (who was not married to his mother) and brothers. He later became an assassin. At first his targets were Japanese; after the occupation ended, he murdered Indonesians in the service of the Dutch, without question, without any pangs of conscience. The source of his loyalty to his overlords, from a country he had never seen, remains a mystery.

In this unsparing family history, Birney exposes a crucial chapter in Dutch history that was deliberately concealed behind the ideological facade of postwar optimism and reconstruction. The influx of refugees from Indonesia formed a threat to this illusion. Those wars turned Nolan from a boy into a monster, at least in the eyes of children. Do the memoirs offer his son a new perspective; does the monster become human? Nolan ends with the words, ‘I won’t fight anymore; I quit.’ But of course he cannot quit, and readers of this superb novel will likewise find that it reverberates long afterwards in their memory.