Books

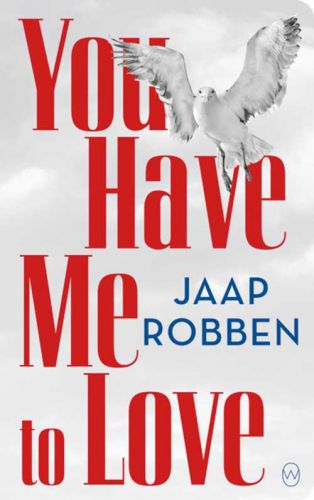

You Have Me to Love

You Have Me to Love by Jaap Robben, translation: David Doherty

(World Editions, 2018, 248 pages)

Jaap Robben is well-known as a poet, children’s author and theatre director. This, his first novel, is set on a remote island between Norway and Scotland. Only one family lives there – the nine-year-old Mikael and his father and mother, plus a solitary neighbour. The mail arrives every week by boat. One day fate strikes: Mikael’s father drowns after saving his son from the sea.

It happened by the rock that his mother had often warned him about. The rock I must ‘never-never-never, look at me, never jump off.’ By keeping quiet about what happened, Mikael – who at the time of the fatal event is nine – hopes to change reality. It is some time before the reader learns the truth about what happened. In a penetrating way Robben gets under the skin of a boy who is consumed by guilt, uncertainty about the future and confusion about how to deal with his grieving mother.

The book sparkles with short sections of dialogue. The conversations are marked by periods of silence, and it is precisely this silence – which can descend at any moment — that is very telling. The conversations between mother and son in particular reveal the gradual souring of their relationship. ‘We came no closer than opposite sides of the table.’ Such gems – sentences, similes or images – can be found on almost every page.

Mother and son drink ‘awkward coffee’, a ball smells of ‘new raincoats’. Or take a sentence like this: ‘With the naked eye, the sail was as small as a folded piece of paper, but with my binoculars I could see that there was someone standing under the boom with a red coat on. There was someone else in a blue coat fore. I focused and saw that it was the plastic case for the jib.’

The reader can’t help but feel stifled by the mother’s psychological warfare, the way she boxes her son in with passive aggression, but elsewhere seems to be trying to seduce him – Mikael reaches puberty in the course of the story – by walking about the house naked and creeping into his bed. Is she looking for a new husband in her son, or does she want to punish him for the loss of her husband? That is the key question, which eventually leads to a dramatic finale.

A bold, tender and ambivalent narrative, raw and disturbing, with moments of painful beauty. – Irish Times